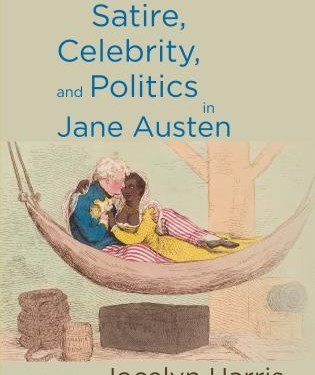

Satire, Celebrity, and Politics in Jane Austen, 2017.

Order

Now available in hardback and paperback.

Also available from Jane Austen Books, Bucknell University Press, University Book Shop and other usual online book retailers.

Reviews

… an impressive new book … a well-written, deeply researched, and timely book [which] has a great deal to offer … important point … provocative picture … incontrovertible point … Harris’s fascinating, suggestive arguments are made in brushstrokes both wide and fine … detail-rich and allusive … repay close reading … Especially engaging … most brilliant parts of the chapter … intriguing … original and important … tour de force … quite simply superb. It is difficult to find any scholarship on these subjects that is simultaneously attentive to Austen’s fiction, to the history of theory and criticism, and to the minutiae of Austen family history and biography, Harris weaves together all these kinds of evidence and arguments together to great effect. … Harris’s argument are highly illuminating. For years to come, readers and critics will be weighing the massive number of new insights in this book, troubling through their implications for our future readings of Austen, politics, history, and popular culture.

Many readers will initially be skeptical of Harris’s claims about Austen as a “celebrity-watcher” who frequently based characters on famous figures, and many will be put off by the frequency of usages such as may have, could have, if, and perhaps. But Harris’s astonishingly rich knowledge of the newspapers, cartoons, and personal correspondence of Austen’s time really does permit her to present a new Austen. In Harris’s showing, Fanny and Susan Price of Mansfield Park owe much to Fanny Burney and her sister Susan, and that novel’s Lieutenant Price channels Susan Burney’s coarse, brutal husband, also a marine lieutenant. The Bertram sisters owe something to George III’s daughters, and the theatricals owe a great deal to similar scenes in Maria Edgeworth’s novels Vivian and especially Patronage. Most all of Austen’s less-than-admirable male characters, from Northanger Abbey’s John Thorpe and General Tilney onward, convey oblique jabs at the regent himself…. [T]his is a wonderfully rich and convincing presentation of much new material. Summing Up: Highly recommended. Lower-division undergraduates and above.

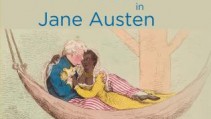

New Zealand academic Jocelyn Harris’s excellent Satire, Celebrity and Politics in Jane Austen published early this year shows what a keen political observer Austen was, and how her interest in the celebrities of the day, such as actress Dorothea Jordan and Sara Baartman (an African woman with very large buttocks who was exhibited in English freak shows as “the Hottentot Venus”), influenced and inspired characters in Austen’s fiction.

Jocelyn Harris is an excellent writer …. This book is an enjoyable one for anyone who has read Austen’s novels or watched productions of them on television …. For an academic study, the usual jargon and allusions to various post-modern theories are happily absent in this book. It is packed with detail and citations. It’s is valuable for Cook enthusiasts because of its chapter on Molesworth Phillips, and the broader considerations surrounding the death of Captain Cook.

The book aims to expand our ideas of the nature and bounds of the society Austen knew. The web of acquaintance, coincidence and proximity conjured by Harris is a marvel, and the surprising juxtapositions it produces will certainly inspire fresh thinking about the novels.

Satire, Celebrity and Politics is unfailingly fascinating in its dissection of Jane Austen, the satirist, and the text is enhanced by a well-chosen selection of contemporary portraits and gloriously scurrilous cartoons. The “stories behind the stories” always make for an interesting read and Harris has produced a book that will be read with great pleasure by academics and devoted readers alike.

Jocelyn Harris’s book. . . is a pleasant and accessible read. . . . I would emphasise the thorough research into the socio-historical context that has gone into this book, and which makes it of interest to anyone who would like to know more of current events during Austen’s lifetime.

Burney scholars will find Jocelyn Harris’s latest book Satire, Celebrity, and Politics in Jane Austen an enriching read. . . . [the book] testifies to the wit and ingenuity of a novelist who “both plunder[ed] and swerve[d] away from” her contemporaries, thereby both honouring and surpassing them (106). Addressing a variety of topics discussed in Austen studies, Harris reinforces the image of Austen as a well-informed and sharp-minded woman who was seriously engaged with the socio-political issues of the day. Most of all, however, the book gives shape to an Austen who was an avid and grateful consumer of the latest gossip, scandals and satirical prints about those from whom she was never far removed: famous writers, intellectuals and actresses, big naval figures, the royal family. With a keen eye for detail, Harris exposes the subtle connections between the unrestrained, public laughter surrounding such figures and the more restricted, oblique laughter in the novels, thereby deepening our understanding of Austen’s skill for satire in the process.

Throughout Satire, Celebrity, and Politics, we are thoroughly persuaded of Harris’s main argument that Austen “was a politician, in the former sense of a person keenly interested in practical politics,” whose awareness of politics not only fuelled her creative process, as she drew on particular controversies for her texts, but also charged her novels with political currents as she penned commentary on slavery, sexuality, patriotism, and women’s education through her oblique but nonetheless lacerating satirical allusions …. By foregrounding the celebrity backstories that influenced Austen’s writing process and helped her generate her biting satires, Harris illustrates how what we read as personal or domestic events within Austen’s works are actually microcosms of and therefore energetically engaged with the larger political discourses central to Austen’s day. Through these allusions to celebrities, Austen need not provide literal representations of political events with scenes of the slave trade or war—an absence for which her critics long faulted her—to join in discursive debates that align her with abolitionists and feminist public intellectuals. This relationship to politics lends new meaning to the quips about writing upon a little bit of ivory or only being concerned with three or four country families, as we see how politics emerge from her representation of even a select few characters …. Through capacious research, Harris connects the dots between the people to whom Austen wrote as her “most political Correspondents,” the families to whom she was proximate, the newspapers she read, the libraries to which she had access, and the sights she saw to show the great likelihood that Austen was indeed aware of these celebrity controversies: Frances Burney’s lonely time at court, the Prince Regent’s bailouts by Parliament, Dorothy Jordan’s unconventional intrigue, Duke Clarence’s vehement defence of slavery, and Sara Baartam’s eventual role as a figure for the abolitionist movement. Harris reconstructs the historical context around letter writing, circulating prints, and visual caricature to further materialize the extent of Austen’s probable awareness. Harris poses questions to open up rather than foreclose interpretations, asking, for example: “If I am right about Pride and Prejudice, Austen’s sympathies lay with the wronged Dorothy Jordan, so might she have seen the similarity between a mistress and a slave?” (286); “Or might Austen have made of Miss Lambe [in Sandition] an instrument to satirize English society, especially its attitudes to race and slavery?” (263). Harris is careful to qualify the definitiveness of Austen’s intent by noting multiple times how the loss of correspondence during key revision and publishing periods leaves “any connection” between celebrity lives and Austen’s novels “not proven,” but as we follow her through her carefully constructed archive, we find ourselves energized by the interpretive possibilities made available through this contextualization and close reading (239).

Harris shows the inherent political nature of Austen’s satire by smartly linking her with the Hogarthian tradition of caricature—a connection usually reserved for other nineteenth-century authors like William Makepeace Thackeray and Charles Dickens. And by delving into the historical context of satire as signifying “the common slippage between education, outspokenness, and transgression in women,” Harris considers Austen’s embrace of satire as a subversive move that even more squarely places her in the gender politics of her day (153). Harris’s monograph ultimately leaves us with two questions, one explicit and one implicit: What if Austen’s lost correspondence was political rather than personal? And what would Austen think of celebrated figures today?